[Initially published on susam-sokak.fr on April 2, 2011. Slightly modified and translated, June 2020]

A person's attire can act as a banner. As at any Kurdish manifestation or feast I witnessed, when women suit up with traditional clothing in the colors of the Kurdish flag: green, red, white, yellow. These women are flags. And when worn by a group, the attire can nearly change a festival into a demonstration of protest. The clothing's singularity catches the camera's lens as well as the eye: press photographers are on the lookout for this kind of visual message. It is in fact part of a communication system, in which a sign is recognized as such, treated as such by the media (photographer, editorial board, page layout, or publisher), and finally recognized as such by the recipient (newspaper reader, viewer). As any communication process does, this semiology acts on the accordance of the ability to recognize the sign, of interpreting the addressee's intention, and on the existence of shared knowledge (the reader/viewer's ability to interpret the sign, his staging by the addressee and then by the media). The message is transmitted through the image – even implicitly, by the image only, when the title, subtitles, picture caption, and the report, are mute about the message itself.

The Kurdish attire is only one case among others. The type of Islamic woman veiled in black is another example, which works perfectly as a sign. It deals with a female "Islamist" outfit, covering the entire body and part of the face with a black cloth (kara çarsaf). Curiously, this clothing is reminiscent of a Turkish urban fashion of the 1920s: Mustafa Kemal's own wife, Latife, appears dressed in this way, alongside the future Atatürk, in the period's photographs (a fact the "Islamists" do not fail to recall of when the constraint on clothing is stronger): she is covered with a black chasuble, and a scarf surrounds the top of her head until the forehead, masks her cheeks and her neck up to her chin, and letting appear from her face only a triangle.

At the end of the XXth century, black dress was frequent only in certain districts of large cities (the Fatih district in Istanbul, for example). Elsewhere, it could be seen only in certain circumstances (women's groups around mosques, Islamist cultural or political events such as the Üsküdar book fair, or the major demonstrations of political Islam of 1996-1998). The wearing of the kara çarşaf drew attention all the more as it was worn in groups. In the period's context of a confrontation between Islamism and secularism, whatever the motivations of the women who wore it, and whether or not they had been forced to do so, the black attire had a semiological effect; even if it did not express an intention on the part of the women who wore it, it was perceived as such, either in cities or neighborhoods with an "Islamist" majority (as a sign of conformity to an order), or on the contrary in rather "secular", "Kemalist" cities or districts, where it had a provocative connotation. And this perception by secularists made women in black a target for press photographers. In fact, the presence of a woman in black marks a territory, either because she grows like a plant on the soil of an "Islamist" neighborhood, or because, in a non-Islamist context, she reminds us of the existence of this current, of its capacity to conquer, in neighborhoods that are not of its own: in sum, either a sign of conquest accomplished or a sign of threat.

Moreover, in the eyes of the "secularist" trends, the woman in black represents, more than any other sign, the past, the reaction, the backward step that would be political Islam, particularly in Turkey in the context of the - at the time prevailing - Kemalist teleology in which history is seen as a long march towards secularism and modernity. The presence of the woman in black in "modern", and "western" districts such as Beyoğlu (Istanbul) was seen as inappropriate. Similarly, the presence of women in black near the very symbol of modernity, namely Atatürk and his representations, is interpreted more as a paradox, as a provocation, even more as a sacrilege.

As a result, press reports have often given preference to the woman in black, rather than to other clichés. To cover an Islamist demonstration in a "secularist" newspaper, for example, a picture framing one of these women or, better, a group of them, was welcome; it was supposed to image the subversive nature of the demonstration, of the demonstrators' desire to transform or overthrow the established dress order, which is merely the metonymy of the Kemalist order. In short, the image of a woman in black, in a secularist media around 1996, serves either to frighten or to ridicule, two forms of political struggle aiming at the same goal.

Here are a few examples, and let's start with a tasty episode.

The Stone Age

The foreign policy of the Islamist coalition Refahyol was one of the main grievances of the Kemalist opposition, as Necmetin Erbakan had multiplied the signals towards countries that are dubious to the eyes of the secularists, such as Iran, Libya, Malaysia... Thus, in December 1996, Iranian President Rafsanjani was paying an official visit to Turkey.

Women from the Iranian delegation paying a visit to Turkey. Photo published in Radikal, December 20, 1996

On December 20, 1996, the leftist daily Radikal attacked this policy in an amusing way. As several women from the Iranian delegation, including the wife of President Rafsanjani, are visiting the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, the photographer, Adem Altan, shoots them examining a showcase concerning the age of cut stone (Yontma taş devri). The picture caption, "A glance at the age of cut stone", is ambiguous: is the "glance" the one these women have at the window, or is it the reader's glance at these women, assimilated by their dress and everything they represent, to prehistory? "Their attire, says the text, is an appeal to modernity". The woman in black, in this cliché, is devoid of humanity: she is only a vague form, as it were without a body, and without a face: a bag. Is this a way of saying that Turkey is at risk of the same fate as Iran?

On December 22nd, Kemalist-laicist Cumhuriyet illustrates the event and mocks the Iranian delegation with a drawing of Ulvi (Ali Ulvi Ersoy, 1924-1998), inspired by the visit to the museum. In the showcase, a man is preparing a fire by rubbing wood. The visitors are dressed in black chasubles and scarves, like on the photograph. But Ulvi interprets the fact more ironically: instead of giving them the aspect of a bag - as it is the case on the photographs - he don't forget that actual women live under their attire. He lends them a semblance of a face, almost uncovers their ankles, and even makes their buttocks stand out!

In the same vein as in Radikal, Ulvi makes them say: "What a long way humanity has come to our level of civilization, hasn't it, sisters?". For the caricaturist, they don't even realize that they, too, are from the Stone Age. "A return to the Middle Ages", the rhetorical figure usually used to denigrate Islamism is outdated: it would be a plunge into Prehistory.

The women of the Iranian delegation offered a wonderful opportunity for mockery. But on Decembre 25, 1996, the Islamist daily Yeni Safak tried to ridicule "secularist" journalists in their turn. Under the title "The Photographic Acrobatics of Professional Atatürkists", Selahattin Yusuf tries to take the rhetoric apart: "They were on the lookout for a good shot, they got it". And to compare the micro-event and its treatment to another, he mentions a swimsuit fashion show in Batman (Southeast of the country), which was described by the reporter of Hürriyet as a symbolic victory over Islamism. But Selahattin Yusuf falls himself into the opposing stereotypes, for the message of these journalists would be, as he writes: "Cursed be the veiled women, long live nudity, and to the end!”. According the caricatural views of the opposite sides, the alternative, for Turkish women, seemed to be either to be fitted in black clothing, or nudity.

The woman in black, a figure of the Islamist protest

On July 21, 1996, Sabah, like other mainstream newspapers, reported on the 13th-anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Refah Party, the freshly-elected party in power. A photo report by Ali Ekeyılmaz, was supposed to present readers with "The Refah's Face". Five images carefully targeted the audience, so as to guide the reader's opinion. In the Islamist sphere, and under such circumstances, genders usually are separated: this is what the opposite side mocks as a haremlik, the space dedicated to women in Ottoman houses and palaces (another way of sending the Islamists back to the past). Out of five images on this page, one of them "represents" the male public, while the others frame the female audience. For the male side, the photographer has framed two men with long beards wearing turbans; thanks to the telephoto lens, the very narrow field of the image gives the impression, at first glance, that the audience is made up of bearded people. But if one looks closely at the background, most of attending people are with hairless faces or the usual thin moustache.

The photographer made a similar choice for the female audience, but he used a wide-angle lens, allowing him to photograph very closely women in the front row, while the persons in the following rows are perfectly distinct. As on the men's picture, one can observe that the women's outfits mostly are of the standardized "Islamic" type, which one is used to in all places and all strata of society: long skirt or dress, colorful headscarf more or less severely framing the face. But in the front row, two women, among the dozens who are visible, are dressed with a black dust cover (kara çarsaf) which covers the whole body, and a black shawl veiling the head, the nape and the lower part of the face - just as Latife Hanım's attire on the photos of the twenties.

The women in black cover more than one quarter of the image's field, so that their presence makes them the very subject of the photograph. In addition, the photographer, using a telephoto lens, has shot another close-up portrait of one of these women in black, whose eyes are also masked by large sunglasses; she is accompanied by a young boy with a green headband bearing a verse from the Koran. Finally, the boy is isolated in a third snapshot, whose caption is: "Headbands in Arabic". In Turkey, the Arabic script has a semiotic charge referring to the idea of "religious reaction" (irtica), and reporters usually do not even want to know the meaning of the text, but here it is transcribed in Latin Turkish script: "Lailaheillallah Muhameddün Resulullah". The woman in black, the boy, and incidentally the two bearded men are the subjects of the whole page: four people represent "the Refah's face". The photographer's choices obviously did not escape the attention of the audience: the neighbor of the woman in black, astonished, turns to the latter; other women in the background seem to find the scene amusing. In the background, no other woman in black is visible.

The photographer, and then the newspaper's editorial staff, treated the information in order to frighten the reader. The veiled face of one single woman, preferred to hundreds of others, was chosen as emblematic. The Refah had been in power for a month, in coalition with the DYP, and the secularists (in this case two-thirds of the electorate) were afraid of what might happen, possibly Iranian-style Islamism.

The newspapers having sympathy, even moderate, for the Refah, produced other iconographic interpretations of the theme of the "Islamist" crowd. On May 11, 1997, a huge demonstration was organized on Sultanahmet Square in Istanbul to defend Islamic societal values, including the right to religious education. The demonstration completely filled the immense esplanade between Sultanahmet mosque and Aya Sofya. To give an idea of the human mass, the newspapers showed, as well as aerial photographs, clusters of demonstrators perched on the trees, or on the domes of the türbe (mausoleums) and fountains in the square.

The far-rightist daily Türkiye, and the Islamist Zaman, illustrated the event by choosing pictures with a predominant red color. As a matter of fact, a large number of demonstrators waved the national flag or even wore it on their shoulders, in order to express their belonging - despite their opinions - to the Turkish nation. On the front page of Zaman, for example, red was the dominant color, as it is used to be on the front page at each national celebration. The daily Türkiye is neither Islamist nor "secularist". It expresses the views of the nationalist trend called "Turkish-Islamist synthesis", where Islam is seen as the essence of Turkish identity and nationhood.

In this spirit, to illustrate the event, Türkiye's photographer Levent Akın has made a very different image from those described above. He chose to frame a very homogeneous mass of young girls in ordinary outfits of "moderate" Islamism, long skirts, and colorful scarves, and where a largely smiling face draws the reader's attention. In fact, the main subject of the cliché is a young woman in a long black dress (but not the ample black veil or kara çarşaf) with white sleeves, colorful scarf, apparently perched (but this seemingly is the result of a montage) on the shoulders of another demonstrator, or on invisible support, above the crowd of her mates; and, like all the others, she waves the national flag. Again, the general tone is red. If you look closely, however, you can make out a small dozen women in black on the picture. But they are almost invisible, very much in the minority, and clearly, this group is not what the photojournalist was intended to show: his will, or the redaction's will, was to produce an image of nation and religion, of the “Turkish-Islamic synthesis”.

This demonstration took place during the final period of Refahyol's government, between two significant episodes of the 1997 "soft coup": the meeting of the National Security Council on February 28, and the General Staff's press conference on the "religious reaction" of June 11 (irtica brifingi), two significant days when the army made its pressure and threats against the Islamist regime. By the way of its photographs, Türkiye expresses its position: the Islamist movement is legitimate and so is his claim for "freedom of education," which supposedly was threatened by the February 28 directives. "This population belongs to the nation, its opinions are modern - not "medieval" or "retrograde": such is the iconographic message. Thus, the above-mentioned image frames a "normal" population, with women showing their open and smiling faces. There is no discernible threat on the picture. Besides, as we personally were on the spot, we weren't struck by the presence of women in black. Cartoonist Turhan Selçuk, from Milliyet, however, had chosen to represent the demonstrators only by a terrifying group of women in black.

In these times of fierce confrontation, secularist media see women in black everywhere; they go looking for them where they are and multiply them where they are few. The woman in black is the perfect object to frighten, as shown by Selçuk's caricature.

Let us refer to the last example: after the Refahyol government resigned (June 30, 1997), the Anasol government of Mesut Yılmaz (center right) and Bülent Ecevit (moderate left) began to implement measures aiming to hinder religious education (the most important being the "Eight Years Law"). In reaction, demonstrations were held in favor of private religious high schools (imam-hatip). On October 12, 1998, Islamist circles (first and foremost the Fazilet party, which replaced the dissolved Refah) organized a "human chain" linking Turkey's extremities. The event was called "Hand in Hand for the Respect of Faiths and for Freedom of Thought". Without achieving its goal of forming a 1300-mile chain, the operation was spectacular in Istanbul, where we could follow the chain from the Galata Bridge to the Bosphorus Bridge. Along the chain, we could see a variety of outfits but few women in black.

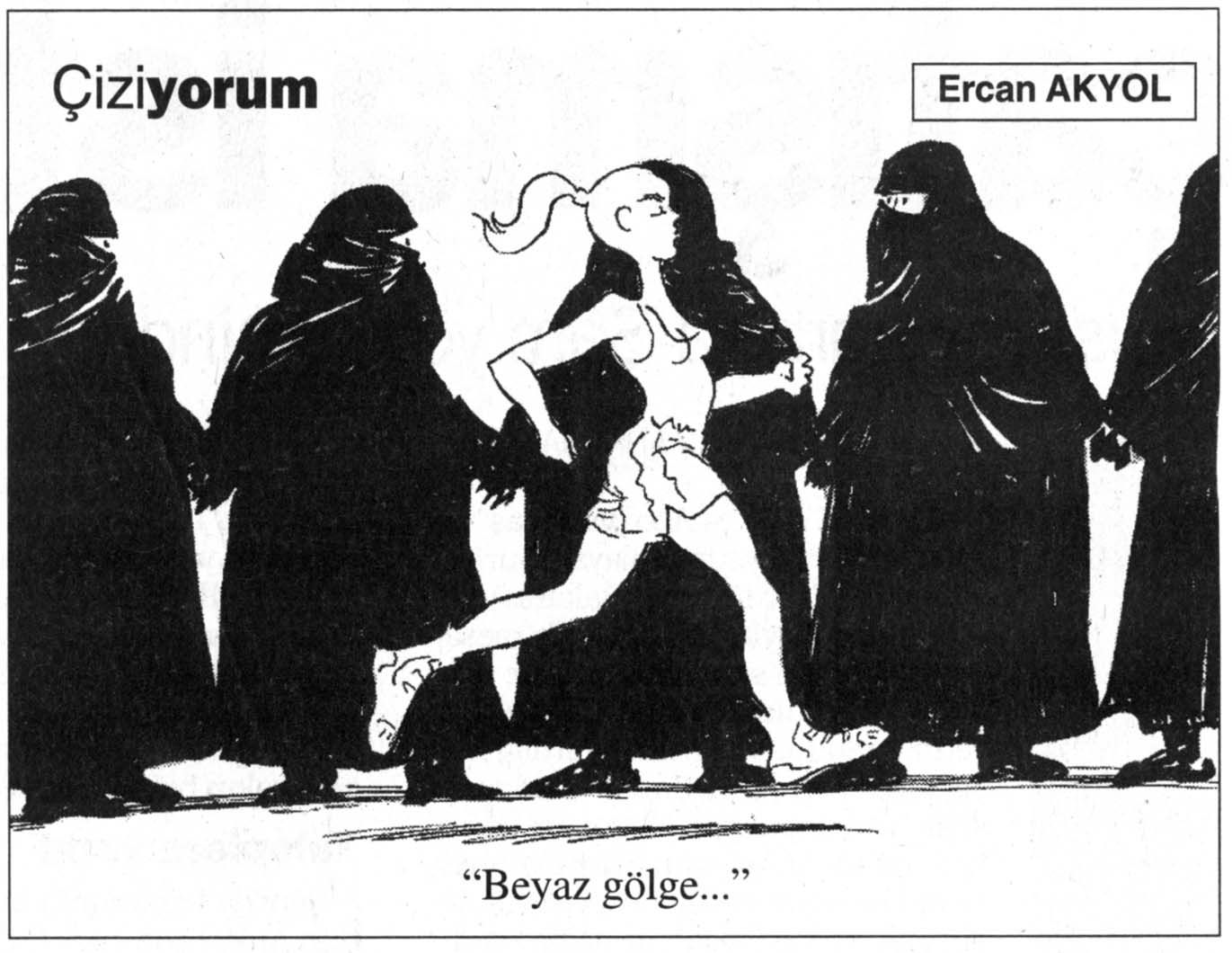

In the press reports, the photographs confirm my personal memories by the rarity of the color black: two women in black, tightly framed, on the front page of leftist Yeni Yüzyıl, and three in Milliyet. But all the photos framing large groups, whatever the media, reveal a weak presence of this attire. Yet Ercan Akyol, a cartoonist of Milliyet, seems to have seen only women in black, and only draws women in black. The same day was also the day of the Istanbul marathon, and the two events did indeed cross paths.

Ercan Akyol made it the theme of his composition, nicely entitled "The White Shadow". Women in black holding hands, their faces veiled, form the background, the decor of his drawing. They contrast with a lightly dressed blonde marathon runner running past them: the White Shadow. The veiled women look at her in amazement. Sport, the female body, and even the blond woman herself, represent here the antidote to evil, Kemalist modernity.

/idata%2F1401155%2F97.07.31-cesur-k-z-1-sa.jpg)

Chantal Zakari, Mike Mandel, Atatürk... - Susam-Sokak

dernières modifications le 20 décembre 2014] Dans le travail que je fais sur les années 1990 en Turquie, de nombreux événements et personnages de l'époque me raccordent au présent ; l'affair...

http://www.susam-sokak.fr/article-chantal-et-mike-67573223.html

On the same topic, see also "Chantal Zakari, Mike Mandel, Atatürk... " (in French)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221116%2Fob_011b69_96-05-30-hrt-fatih-e-fetih-c-ic-egi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221019%2Fob_f0c0d3_96-05-27-hrt-izleyenler-gerc-ek-cop.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221004%2Fob_0ad148_ob-f62150-98-05-29-tg-fetih-copie-2.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20201113%2Fob_e935fc_15099884742-ataturk.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230405%2Fob_981fa4_taksim-couv-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230311%2Fob_9e11bf_96-02-25-tg-boya-attilar-copie-copi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230127%2Fob_477ec5_98-06-23-miting-gibi-cenaze-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230109%2Fob_ce8477_ku-rt-boyu-la-carte002-copie-copie.jpg)