[Initially published on susam-sokak.fr on September 5, 2010. Revised and translated in July, 2020]

In France, publishing a photograph of a corpse remains taboo. This is perhaps the reason why some images picked out of my corpus drew my attention. In the frame of a conflict, a public display of corpses is intended to intimidate and terrify the population. Even in Turkey, though the related taboo is weaker, corpse exhibitions are not often reported in the press, but such a fact was pointed out by Hikmet Çetinkaya, a journalist of Cumhuriyet, on August 11, 1997: two corpses of "terrorists", he reports, had been carried on a car down in the streets of Hakkari. Combat had just occurred in the neighboring, and when the army spokesmen announced 25 casualties on the Kurdish side, the population of Hakkari had refused to believe them. The army, therefore, provided "evidence". This initiative turned the journalist off, who asserted that the power would get nowhere with such “inhuman methods". But it is an isolated voice here, as Çetinkaya's indignation was not echoed by other journalists, neither that day nor, as far as I know, some other time. Inasmuch as the major part of the Turkish media remain respectful of the army, a protest like Çetinkaya's, even timid, is all the more commendable.

Reporting the exhibition of corpses, without any hindsight nor blame, fits well the orientation of the far-rightist daily Türkiye whose reporters in such cases write exactly as if they were the army spokesmen. "The End of a Terrorist": the picture above was published by Türkiye on September 3, 1998. As it is uncredited, it may have come directly from the army. The corpse of the “terrorist”, a young woman, lays on a tarpaulin. Without any visible wound, her body seems not damaged, nor does her face, turned towards her left side, towards the photographer. Her eyes are wide open, looking calm as if she were resting or daydreaming. Is she a female Sleeper of the Valley, a Dormeuse du Val? Her body's posture belies this impression: her feet, turned sideways in a constrained position, wouldn't stay that way if they belonged to a living and relaxed human body.

She is displayed there like an object, without any respect from the military, nor from the press. A plaque or fabric band, on the extreme left of the picture, where the letters J-A-N, for “Jandarma”, can be read, is traditionally used by the armed forces to sign a military deed: the trophies taken from the enemy are usually arranged on a table or, as here, on a tarpaulin, to be presented to the photographers. “Jandarma”, the gendarmerie, is a key element in the war against the Kurdish rebellion. The trophies are displayed in perfect order, as usual: a rifle, a belt, and a shoulder belt, rifle loaders, and the young woman herself, who wears a trellis jacket and combat trousers. Her waist is girdled with the traditional Kurdish scarf. Her dream, the independence of Kurdistan, is over: her body is reified, made into a trophy among other objects. As the picture's caption goes, the young woman was "taken killed" (ölü ele geçirildi), killed while fighting in the Zara region, during a skirmish that also caused the death of one gendarme, one village headman (muhtar), and four civilians.

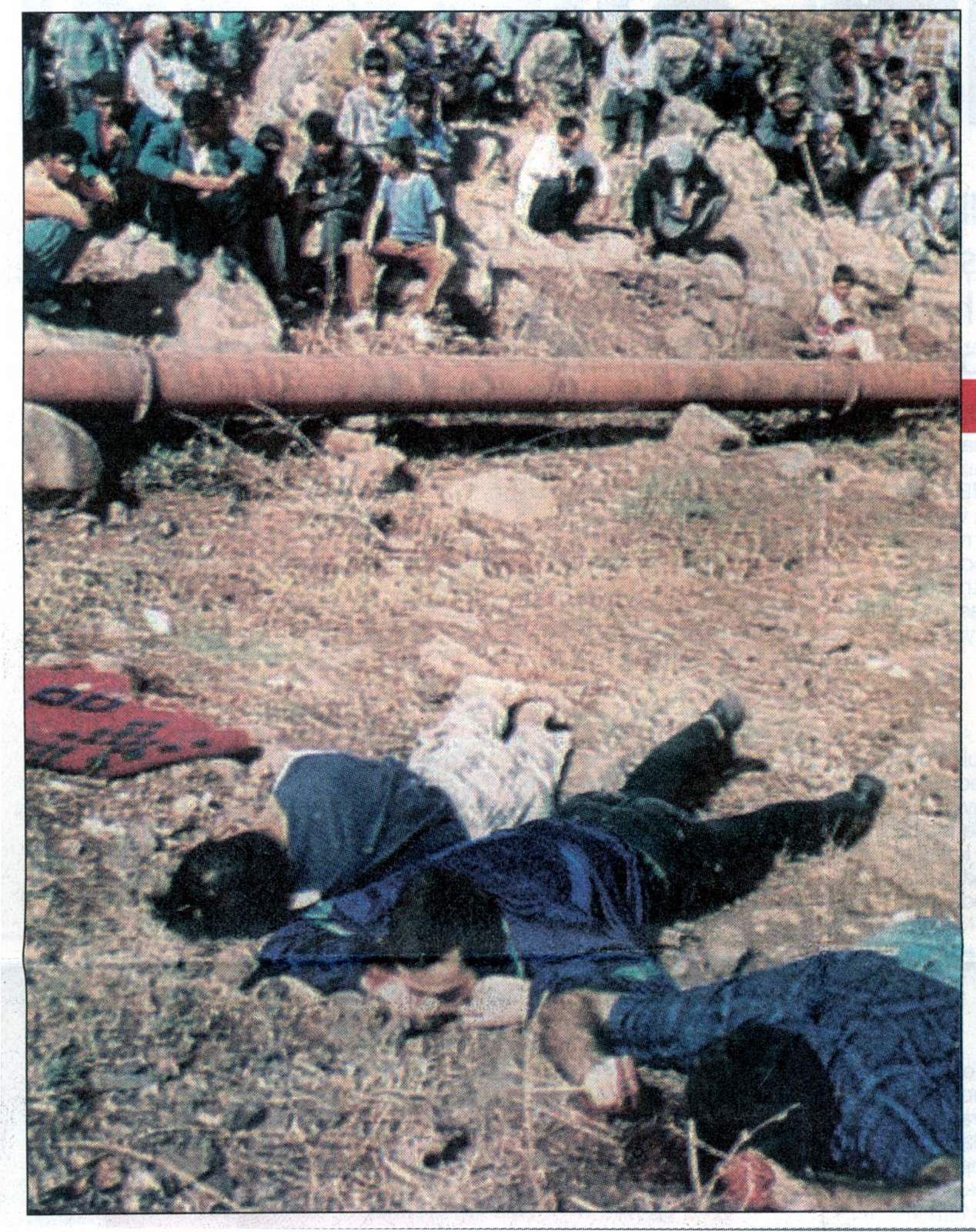

Another picture published by Türkiye is even more shocking, not because of what it shows, but because of the practice the article illustrates. One day in March 1998, four bodies of "separatist fighters" killed by the "security forces" are exhibited to the population, on the scquare of Kale, a village in the Southeast. Again, it's a trophy exhibition. Behind the bodies, rifle butts are barely visible in the picture field. The fighters wear çalvar, the pants of the Kurdish fighters, or a battle dress. Oddly enough, their shirts are pulled up over their faces so that the upper part of their body is bare. Before the shooting, the corpses obviously were covered with a blanket, hastily removed for the photo and for the following scene, because the corpse exhibition is not the only shocking element of the practice represented by Türkiye.

Another picture of the same article (on the left, below) frames a line of men, turning hateful faces in the same direction, on their right. On the far right, an armed soldier and, in the background, another soldier in fatigues, probably a ranking officer, with his hands behind his back, are watching the scene. There, the male population of the village, gathered on the spot, files past the bodies ans spat them; the picture's caption states it as if it were a normal thing.

A third picture shows a huge crowd of villagers shouting their anger – but the photo is most likely a fake, as such a crowd is unlikely in a small village (on the right, above). Armed soldiers - apparently including a woman - block their way. According the picture's caption, the villagers were intending to burn the bodies of the "terrorists", and the army reportedly prevented them from doing so.

What happened in the village of Kale induces some questioning. To begin with, the villagers did they come of their own will to commit a desecration of corpses, or were they constrained by the military (perhaps not at gunpoint, but by the means of implicit bargaining like “If you don't, you are in collusion with the terrorists”)? Were these uncredited photographs taken by an army official photographer? How may the readers of a media – even the readers of Türkiye – accept such a desecration, organized by the members of the most respected institution in the country? How the behavior of the detachment's officers hasn't met with a scandal or any criticism in other media and/or among the civil society, especially as, at that time, the country was ruled by a center-right/center leftist coalition? The Kale scene is a demonstration of the army's ascendancy over the society, during the 1990s in Turkey. What I use to call the “mandatory consensus” is perfectly working here.

Exhibiting a corpse and broadcasting such images in the media takes part of a language. While exhibiting a dead “enemy” signifies and symbolizes the army's efficiency, and aims to give a lesson and to intimidate the public, in turn, exhibiting a “friend”'s corpse killed by the “enemy”, is a warning, an alert recalling both the existence of the menace and the foe's cruelty. It maintains and, if possible, strengthens hatred. Some murders are particularly shocking, as, for instance, when teachers are killed by the PKK (provided this kind of information to be true). So, at the beginning of the school year of 1996, four young civil servants were assassinated, reportedly by the “terrorists”, and the fact has duly been depicted in the media.

On another photograph published by the daily Türkiye, on October 2, 1996, three of the teachers' corpses are lying in the foreground. The picture's field is barred by a water pipe, beyond which a good part of the village's men gathered, young and elder. A blanket obviously covered the corpses but it was removed for the photo. The villagers are sitting like in an amphitheater, observing the “scene”, simultaneously curious and resigned as if they were expecting something. The teachers probably were civil servants posted there, far from more attractive regions, because of their young age, or of some administrative penalty. Perhaps were they opponents. Their career path stopped there, with a burst of a machine gun.

For its part, leftist Yeni Yüzyıl publishes the portraits of three of the victims, and their names: Sadettin Küçük, Nesrin Idis, and her husband Cuma Idis. The fourth teacher remains anonymous. In another photograph published by the same daily, provided by the official Anatolia press agency, the corpses are lying on the foreground, but the very subject of the picture is a group of three officials in suit and tie, the vali of the OHAL, in other words the governor of the region under state emergency, and his assistants, who came to ascertain the crime. An officer in fatigues comments the scene.

I often wonder if it exists in Turkey a certain habitus, differing from the French one, regarding the representation of human corpses, or, more generally, of a victim, whether living or dead, just after an act of violence, or even just after a traffic accident. At the time when I was living in Istanbul, there was a neat leaning in the mainstream press to represent violence. For example, in the page 3 of the popular daily Sabah, the miscellaneous' page, devoted to bloody traffic accidents, to horrible murders, etc., the red color visually prevailed, as the press reporters used to include in the frame of their pictures wide blood puddles. To photograph a victim apparently didn't give rise to any ethical concern. Horrible shootings framing bodies and even human faces severely injured hurt were very common.

This incited me to pick out of my corpus an image of an incident which happened almost simultaneously, on October 18, 1996. The newspaper is, again, Sabah, and the article is entitled “The thief was about to be lynched”. The photograph frames a man down. He lies in the street, on his back, seemingly unconscious, with his arms and legs spread out. A bloodstain is visible to the right of his shirt. As the daily tells us, this young man was about to steal a car, but he promptly was caught up and severely beaten. He stayed there lying during 45 minutes before a police squad arrives on the spot. No ambulance went there: he was taken to hospital in the police car.

This image is as harsh as one of wartime. The press reporter probably arrived together with the police, and photographed the thief's body lying in the foreground with his avengers all around, standing proudly. The man with mustaches and flowery shirt seems particularly proud of himself. On the left, a young man is smiling for the photographer; on the right, another, hands in the pockets, bubbles his gum. They contemplate the outcome of their job. They have hit a little harsh, indeed. The policemen probably rescued the thief before spreading the crowd. But the journalist – or the daily's editors – instead of criticizing the lynching, qualify the crowd as a group of citizens who did their duty. Not a word is written about the thief's fate: trivial topic.

Is there in fact a relationship between the wartime images and those of such everyday news? Did the war against the Kurds, which then has been going on for twelve years, and even for decades, and, perhaps, did the persistence, in the collective memory, of the genocide and of other mass violence, make the Turkish society so brutal? Or, conversely, does this brutality pervading the social relations for decades – this can be observed every day – make easier an acceptance of the war?

/image%2F5022986%2F20200715%2Fob_e94ce1_98-03-15-tg-tu-ku-rerek.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20200715%2Fob_c89e2c_98-03-15-tg-yakma-istedi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230127%2Fob_477ec5_98-06-23-miting-gibi-cenaze-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230109%2Fob_ce8477_ku-rt-boyu-la-carte002-copie-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221116%2Fob_011b69_96-05-30-hrt-fatih-e-fetih-c-ic-egi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221019%2Fob_f0c0d3_96-05-27-hrt-izleyenler-gerc-ek-cop.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230405%2Fob_981fa4_taksim-couv-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230311%2Fob_9e11bf_96-02-25-tg-boya-attilar-copie-copi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230127%2Fob_477ec5_98-06-23-miting-gibi-cenaze-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230109%2Fob_ce8477_ku-rt-boyu-la-carte002-copie-copie.jpg)