[Initially published on susam-sokak.fr, on June 25, 2011. Updated and translated in English, July 2020]

The rebellion is (in) a foreign country. When the police successfully throws out opponents occupying a monument, or a district, they plant a flag, to signify a conquest, as if the demonstrators had put themselves out of the Republic.

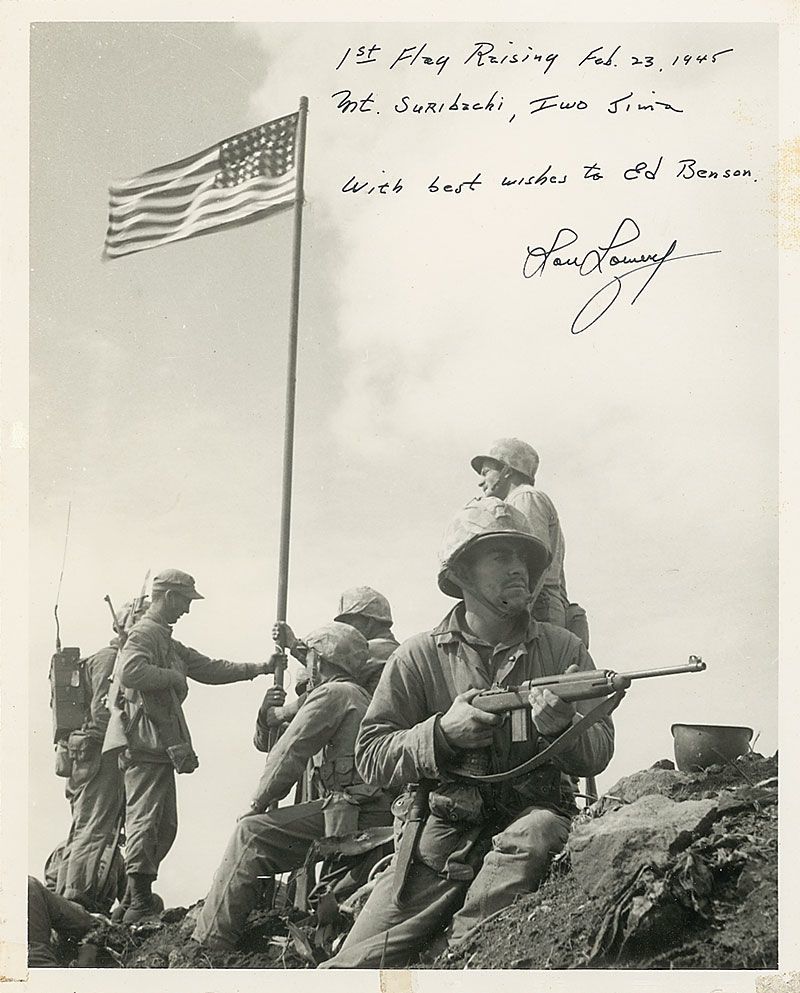

Everybody knows Raising the flag on Iwo Jima, Joe Rosenthal's photograph, taken on February 23, 1945, just after the famous battle of the Pacific War. It is a very controversial shot, which doesn't represent the original scene, since Rosenthal probably has proceeded to a staging. Anyway, it is one of the most famous photographs in history, all the more as it has been re-interpreted as a commemorative monument, the US Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington (Virginia).

The very first photograph of the event (below) was taken by Louis Lowery. The image is by far less aesthetical, but it is nonfictional: the war is visible, with this soldier in the forefront, keeping watch with the finger on the trigger. However, the soldiers who planted the flag in the background seem rather relaxed, attesting to the battle being over. The image wasn't dramatic enough to the eyes of the propaganda services.

In our collective memory, Rosenthal's famous photograph is mingled with symmetrical one, the fitting of the red flag on the roof of the Reichstag in Berlin, on May 2, 1945. Authored by Evgueni Khaldei, this image too is the result of a staging. It was preceded by less spectacular photography, but it became in turn an icon.

Traditionally, fitting a flag or a banner is a ritual signifying the taking of possession, the gaining or regaining of a place, of a territory, at the end of a battle. Among other media, the school textbooks have printed in the memories these icons of Iwo Jima and of the Reichstag, which everybody has in mind and can spontaneously refer to when put in the presence of the image of a victory followed by the fitting of a flag. A more recent and world-famous image is that of New-York City's firemen planting a flag among the WTC's ruins. It perfectly fits with this rhetoric.

But in this case, the sense of the icon may reverse, as it doesn't here signify an actual victory, but a nonexistent one, which remains as a wish, as a will, or as a claim. To say the least, the day of the September 11 attacks wasn't a victory day for the United States. But fitting a flag on the ruins did signify a forthcoming victory and the resolution of attacked country to succeeddd in it.

It was a taking-up of a challenge, an attitude which is not restricted to military or war events. For example, not exceptional are American flags waving on houses destroyed by a hurricane. It's a way of proclaiming "We will get by!". Until recently, this ritual wasn't practiced in France, but it seemingly is spreading out, particularly since the 2015 terrorist attacks.

In Turkey, a well-known photograph illustrates such a ritual which obviously was conceived as a patriotic restorative ceremony and a claim for challenged sovereignty. It dealt with the status, Greek or Turkish, of a small and uninhabited islet, named “Kardak” by the Turks, and “Imia” by the Greeks, close to the Turkish coast of the Aegean Sea. Since in January 1996, a Greek military detachment had planted a Greek flag, Turkey and the Turkish nationalist organizations had protested against what they considered both provocation and sacrilege. If I'm not mistaken, the editorial board of the mainstream daily Hürriyet, was the first to take the opportunity to create a nationalist wake-up.

So Hürriyet promptly organized an expedition on the islet. On January 28, 1996, a helicopter dropped three journalists on Imia/Kardak, where they withdrew the Greek flag and planted the Turkish one. When the photographer Aybars Attila immortalized the scene, he and his colleagues most probably had in mind, even unconsciously, the 1945's “primal scene”. But the image published by Hürriyet is completely lacking in any sense of drama. Both companions are playing again the scene of Iwo Jima, or of the Reichstag, with some bonhomie, and look like retarded boy-scouts preparing their camp. Anyway, as there is no picture caption, the image is ambiguous, as it conversely could be a snapshot of the removal of a Turkish flag and the fitting of a Greek one. The doubt is lifted by the presence, in the picture's field, of the Turkish flame on the helicopter rear spoiler, but the detail doesn't capture the reader's attention.

The Kardak fake ceremony did not seal a victory, since the action moved by Hürriyet conversely brought a crisis, which put Turkey and Greece within an inch of war. During the forthcoming months, the Turkish state, the media of the country, and a good part of the public were extremely sensitive to the flag, its image, its use, and alleged misuse. This phenomenon, which is not specific to Turkey but very striking for the foreigners living there, urged some social scientists to study it (see references below).

The flag is the center of several events unfolding in Summer 1996, still under the influence of the context of the Kardak/Imia crisis. I will restrict myself to two of them. Others, much more serious, like the crisis which erupted on the Green Line in Cyprus, are analyzed in the mentioned article.

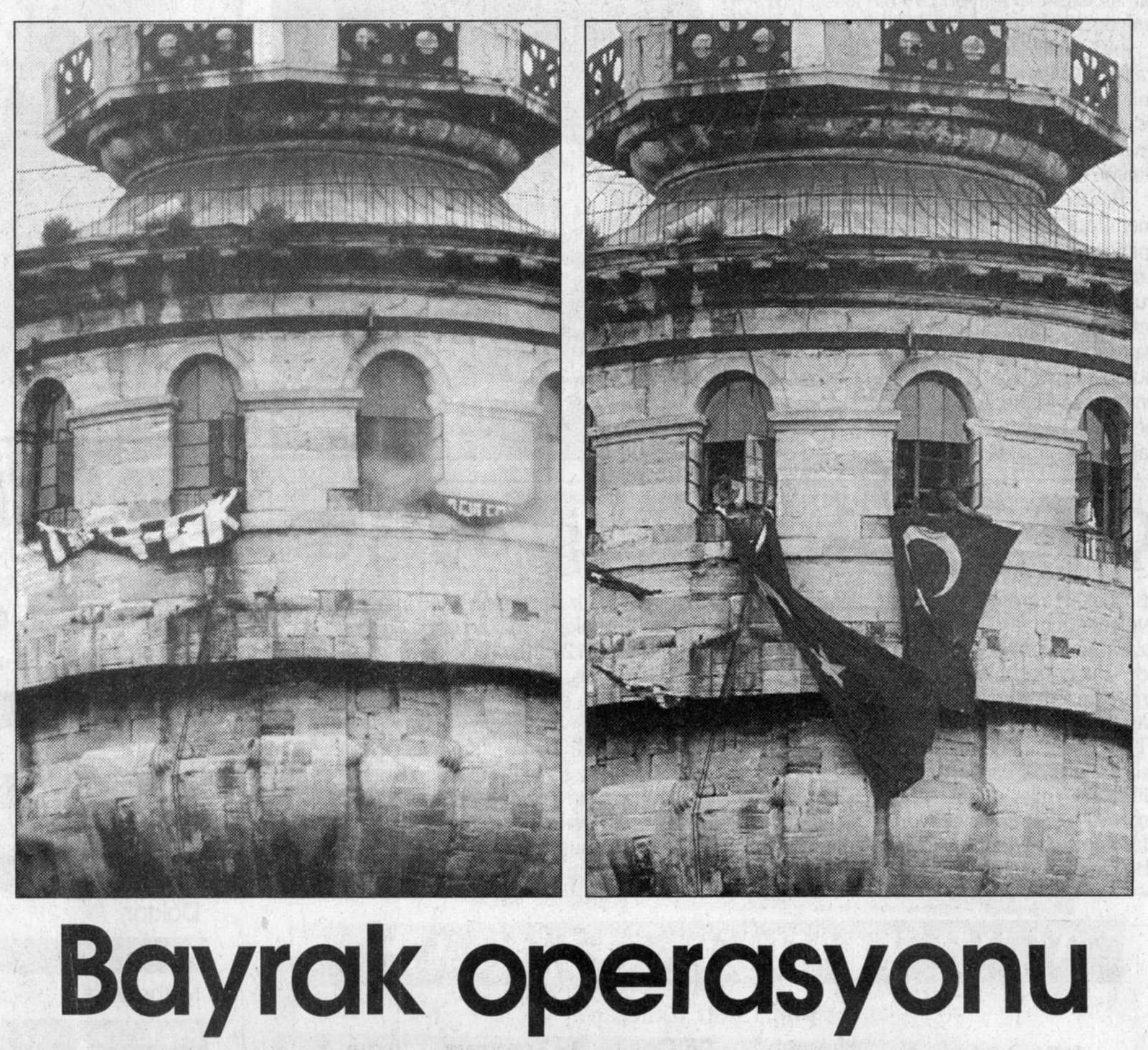

The capture of the Beyazıt Tower

On July 10, 1996, a group of activists of the TIKB (Union of Revolutionary Communists of Turkey), an illegal organization created in 1979, and of its youth branch the GKB (Union of the Young Communards) occupied the Beyazit Tower, located in the courtyard on Istanbul University's main campus, on top of the old city and thus visible from afar. They aimed to draw the public's attention to the movement of the political prisoners, who had initiated a hunger strike in May, to protest against the detention conditions. As the authorities remained inflexible, the strike turned into a drama, since twelve hunger strikers – among them three members of the TIKP – starved themselves to death during the month of July.

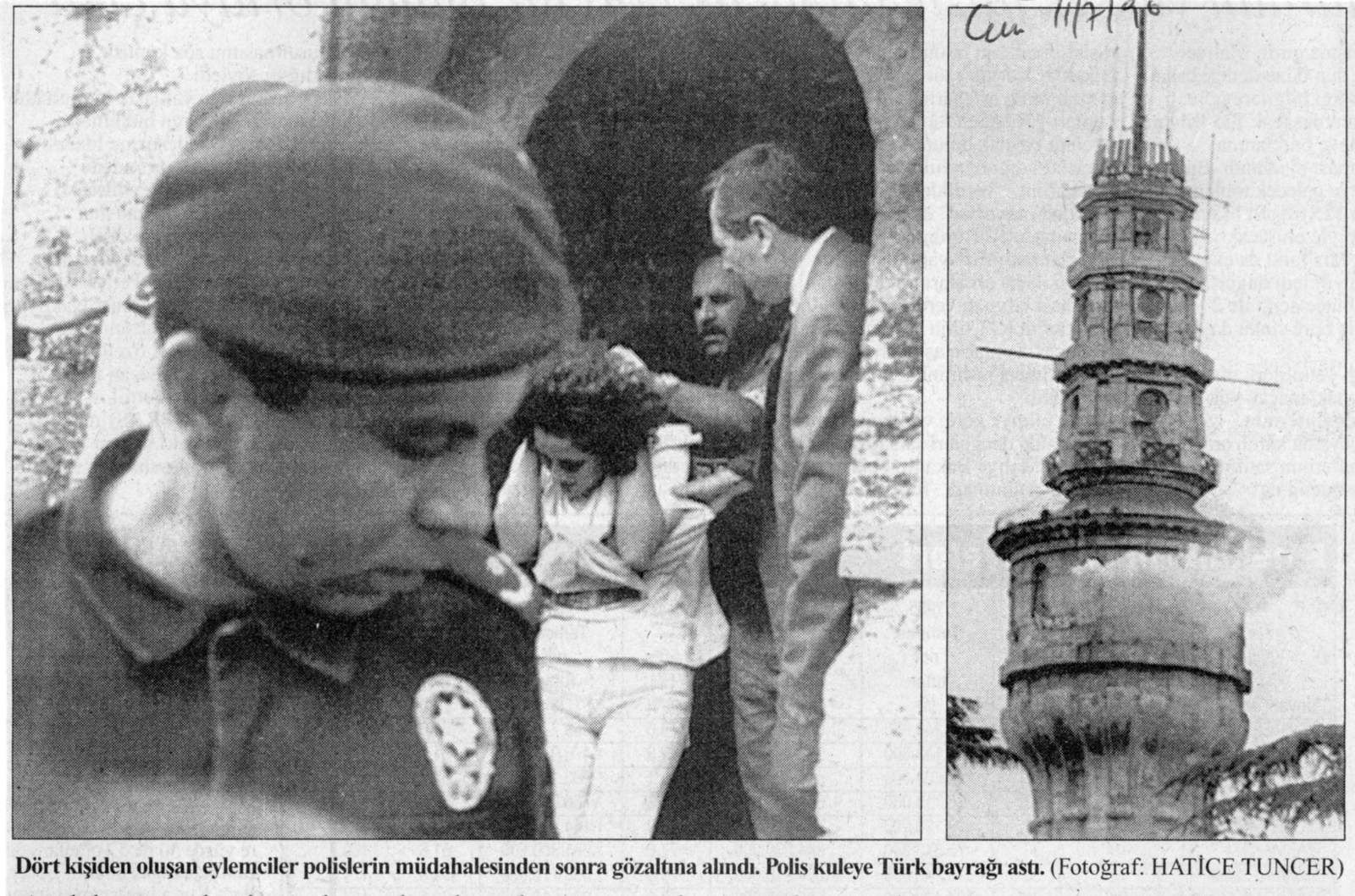

It was a short-lasting occupation, as the demonstrators were removed by the police after two hours. The activists hardly had time enough to set up a banner of the YIKP-GKB. But what has drawn my attention here is the restorative ceremony implemented by the anti-terrorist section of the police, after the “taking” of the Tower. They have set up a pair of Turkish flags, and the photograph of the Tower, before and after the police raid, was published the day after by Hürriyet, as seen above, one of the most sensitive media concerning the topic of the national flag.

Surprisingly, the daily's article, entitled “Operation Flag” (Bayrak operasyonu), does not mention the event itself (an “eylem” in Turkish), that is, a demonstration of support for the hunger strikers, but only reports the police raid and the setting up of the flags, which becomes the event in itself.

What does it mean? On the one hand, the flags, installed for the press photographers, signify a victory of the state on an illegal movement, an inglorious victory probably obtained without any combat. But, on the other hand, this flag story visually asserts the gaining or regaining of territory, even a microscopic one, just as in Iwo Jima, Berlin... or Kardak/Imia. It further means that the state had considered the Tower as diverted from the republic's territory as long as it was occupied by an illegal movement. Is that a reminiscence of the “liberated areas” of the 1970s, these town districts controlled by far-right or far-left organizations, where the state was temporally banned from?. Thus, the Beyazit Tower was a "liberated area" for two hours. There is no evidence that the demonstrators had in mind such a reminiscence of, but it surely was the opinion of the police, since a ritual of re-appropriation of this small “territory” by the republic was deemed as necessary, by the way of flag display. It is a magical ritual, an almost religious restorative ceremony.

Cumhuriyet, a secularist, Kemalist, and more critical newspaper, has minimized this aspect of the police raid, prosaically specifying in the picture caption: “The police displayed a flag on the Tower”. On one of two photographs, a smoke plume, coming from the Tower, is visible; did the demonstrators use some smoke bomb, to draw the public's attention? Or were they thrown out by the means of tear gas? Anyway, the Kemalist daily tries to introduce a bit of criticism inside a well-supervised information, as it is always the case when the police or the army are involved: among the photographs of arrested demonstrators, the editorial board has chosen one of a young woman harshly retained by her hairs, a usual practice, not only in Turkey. The flag's supremacy is somehow eroded by the page layout.

The taking of Gaziosmanpaşa

This "eylem" was followed by other demonstrations in support of the prisoners' hunger strike. One of them occurred in the district of Gaziosmanpaşa (Istanbul), predominantly leftist and alevi, where in March 1995 a provocation had been followed by a strong repression with 17 casualties. On July 17, 1996, a new provocation brought a struggle out with some barricades and tire fires. Several activists had their faces masked with red scarves, what was, together with the fires, was an excellent topic for the press photographers, whose pictures seemingly illustrate a report about a huge uprising.

But if one carefully observes the pictures, one realizes that the fires are very small and that the “crowd” of demonstrators are made by some 30 people. A tire burning is a blessed gift for press photographers since, taken in the proper angle and the right lens, it suggests the district being looted and ransacked. On that day, 17 of July, the police don't interfere. On July 19, Sabah publishes a picture in which some 20 demonstrators are visible: almost a non-event. The demonstrators reportedly were 15-18 years old and displayed banners of “illegal organizations”, which is not verifiable in the pictures.

But on the same day, July 19, the police intervene and take control of the cemevi (the Alevi's worship house) where the demonstration came from. Some leftist banners are then removed and, to put the final dot, a policeman with a helmet sets the national flag on the building's roof (Milliyet, July 20, 1996).

Here, exactly like when, one week before, the Beyazit Tower were “captured”, the fitting of the flag visually expresses the state's victory upon an uprising district erected as a “liberated territory”, in the eyes of the state and probably of the demonstrators as well. It expresses a reconquest, the return of the Gaziosmanpaşa district into the bosom of the republic.

In both cases, the “conquered” are considered as if they had put themselves outside of the republic and of the national community. Outcast are not only the demonstrators themselves, but the radical leftists, and those they give their support to, like the political prisoners, who in turn symbolize the whole extra-parliamentary left, together with the Kurdish and Alevi movements. A posteriori, the fitting of the flag stigmatizes those who supposedly were in a secessionist posture, because they had taken a land fragment away from the republic.

When such scenes are set in images and then broadcasted (often in the newspapers' front page), their significance is strengthened. And the sense of the process is validated by the opposite attitude, when opponent groups (particularly Islamist, during the last years of the century) display the national flag, or even clothe themselves of it, in order to legitimize the legitimacy of their demand and to claim that they are, even as opponents, a part of the national community.

References:

Copeaux, Etienne, and Mauss-Copeaux, Claire (1998). “Le drapeau turc, emblême de la nation ou signe politique ?”. Paris, Cahiers d’études sur la Méditerranée orientale et le monde turco-iranien (CEMOTI), n° 26, 271-291. Online: https://journals.openedition.org/cemoti/633 (Accessed on July 28, 2020).

Seufert, Günter (1997). “The Sacred Aura of the Turkish Flag “. Istanbul, New Perspectives on Turkey, n° 16, 53-61.

/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.openedition.org%2Fdocannexe%2Fimage%2F84%2Fcemoti_160x75.png)

Le drapeau turc, emblème de la nation ou signe politique?

Ce début de recherche sur les symboles de la nation en Turquie prolonge des travaux antérieurs sur la mémoire collective et sur l'image en tant que récit iconographique (cartes analysées en ta...

/image%2F5022986%2F20200728%2Fob_ca3abd_mexico-beach-fla-destruction-hurricane.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20200728%2Fob_832115_american-flag-waving-next-to-house-des.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20200728%2Fob_71ab72_an-american-flag-waves-amongst-the-deb.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230127%2Fob_477ec5_98-06-23-miting-gibi-cenaze-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230109%2Fob_ce8477_ku-rt-boyu-la-carte002-copie-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221116%2Fob_011b69_96-05-30-hrt-fatih-e-fetih-c-ic-egi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20221019%2Fob_f0c0d3_96-05-27-hrt-izleyenler-gerc-ek-cop.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230405%2Fob_981fa4_taksim-couv-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230311%2Fob_9e11bf_96-02-25-tg-boya-attilar-copie-copi.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230127%2Fob_477ec5_98-06-23-miting-gibi-cenaze-copie.jpg)

/image%2F5022986%2F20230109%2Fob_ce8477_ku-rt-boyu-la-carte002-copie-copie.jpg)